🦁 Roar Like A Lady #4 Esther Seligson and a feminist retelling of Homer's Odyssey

A Mexican feminist scholar/writer, and the women who brought her voice to the English-speaking world.

"Will you give me the light of the dawn at dusk?"

- Esther Seligson, Yearning For The Sea

The frightening circumstances of Aghanistan and an unforeseen nervous breakdown have delayed this interview from reaching you and I am very sorry. I am also very grateful for all the messages that I received in my absence with concerns (rightfully) around my disability and I am extremely grateful for an audience that truly cares about me. Disability notwithstanding I’m repulsed by my impotence at being unable to help people not just in Afghanistan but in Algeria, Lebanon and so many other places where life has taken such a traumatic turn.

What I am privileged to do is talk about resilience that is an inalienable part of art, and today an act of pure(gold)resilience. I am so honored to have met Dr. Lewis, publisher at Frayed Edge Press of Pennsylvania and I was struck by her candor - her vast wealth of knowledge and her kindness in letting me take a bit of her time in discussing one of her gorgeous projects, which she edited.

Frayed Edge Press is an independent press located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, which specializes in publishing marginalized voices, overlooked literature in translation, and works that wrestle with important questions impacting contemporary society. I spoke to Dr. Lewis at length on her favourite “babies” and found an inclination towards Yearning For The Sea by Esther Seligson, Translated by Selma Marks.

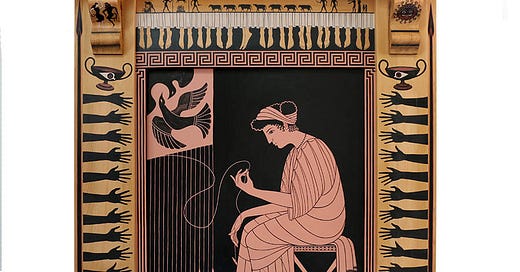

Seligson’s feminist retelling of Homer’s Odyssey centers on Penelope and her feelings of loss and desire. Yearning for the Sea picks up the story at the point of Ulysses' return to his wife Penelope, twenty years after the destruction of Troy. He has faced a long struggle to overcome the obstacles interposed by the gods against his return, while she has worked to hold off her obligation to remarry and provide Ithaca with a new ruler.

What did this twenty-year separation mean to this man and this woman who, after having loved each other in the flower of their youth, are now re-encountering one another as strangers marked by the separation itself? That is the portal through which Esther Seligson enters into a confessional world of the senses, of sexual desire, of love and its absence, of loneliness, and of nostalgia for lost time and lost youth.

I had recently read Circe by Madeline Miller and after reading Seligson - a whole new world was opened to me in the guise of Penelope. I am one of those people for whom empathizing with a character is a very crucial part of the reading process and Yearning For The Sea does not disappoint. I was surprised how until then I had never thought of the why and how of Penelope’s world and I’m so grateful that with each step forwards I meet women who generously show me the way ahead.

Here’s my dewy-eyed conversation with Dr. Alison Lewis of Frayed Edge Press and translator Selma Marks.

Nidhi Ajay: Can you tell us about your discovery of the book and your decision to publish this particular title by Esther Seligson?

Selma Marks: I "discovered" Esther Seligson in the library of the Instituto Cervantes here, in New York City. The very first time that I went there I explained to the librarian I was looking for Mexican authors to translate, would he please help me? He brought me an anthology of Mexican writers and I found Seligson's name there. While growing up in Mexico City I had heard people close to me comment about her bohemian persona and her weird writing. So I took out several books by her, including Sed de mar (Yearning for the Sea), and La morada en el tiempo (Dwelling in Time). Those two books absolutely overwhelmed me.

Alison Lewis: Our “discovery” of Seligson and her work was of course through Selma Marks’ submission of her translation to the press. When I first read her query, I immediately thought, “Yes! This sounds like something we would publish.” Like most people in the US, I had never heard of Seligson before. But her work seems significant to me, and it’s the type of “hidden” or “overlooked” work by a more marginalized voice that Frayed Edge Press is dedicated to publishing.

Nidhi Ajay: The book shifts characters as it moves forward, which makes the tone of voice significantly different with each chapter. How is that process with respect to translation?

Selma Marks: The transition from one character to another is of Seligson's doing. It is her writing--the tone, the terms she uses, the poetic images she creates to build each of her characters--that guided my translation. Her poetic prose might be difficult to translate, but she is very clear about who her characters are, how each of them thinks and feels.

Nidhi Ajay: Why do you think Esther Seligson's radical feminism took so long to enter the English literary landscape?

Selma Marks: Esther Seligson was not a popular writer. Her writing is poetic prose and therefore difficult to follow; to understand it the reader needs a certain level of education that includes knowledge of mythology, religions, history. That is why the circle of her readers has always been small and basically limited to artists and writers. That is one reason why she is not known in the English-speaking world. Another reason is that she is not seen as a Mexican writer. Her writing is highly personal and intimate; except for her rich Mexican Spanish, there is nothing specifically Mexican about her writing. And although she is a feminist, from the perspective of most American feminists (and possibly the more recent Mexican feminism), she is not one of them: she is apolitical, and her "answer" to the subjection of women in a patriarchal society is purely individual and does not involve a thorough redefinition of gender relations in society.

Alison Lewis: Historically, I think there has been a prejudice against Spanish-language works, especially Latin American ones. And of course, women writers have always been marginalized, no matter what the language or the culture. This has been changing more recently, with authors such as Isabel Allende and Julia Alverez becoming more popular and mainstream. But there are still these “hidden gems” like Sed de mar that don’t rise to the same level of popularity, even within their own culture. Seligson’s writing is more difficult, more challenging—but still, in my mind, very worthy of reading and translation.

Nidhi Ajay: What's the most ecstatic moment in a translator's modus operandi, from receiving a project to finishing the last word?

Selma Marks: When I feel that I have been able to get into the writer's mind, and think and see and feel like her/him, and most importantly, that something in me resonates with her/him.

Nidhi Ajay: The femininity of Penelope and Circe are drastically different from one another; did you have to take that into account while translating their characters?

Selma Marks: No. Because the character of Circe in Sed de mar is the product of who describes her in the book. For Ulysses, she is basically a manipulative woman; for Penelope, she behaves like a sister generously sharing with her, her most intimate moments with the man they both loved.

Alison Lewis: I love this explanation. Circe is amorphous, shifting, different depending on who is looking at her. Penelope is in a similar situation, defined through the lens of whoever is looking at her and what their agenda is. It’s not until she really starts looking at herself that she is able to define who she is, from her own perspective.

Nidhi Ajay: In line with Esther Seligson, who are some authors that aren't as popular with English-speaking audiences but should be?

Selma Marks: I have worked on several stories by Eduardo Antonio Parra, another Mexican writer. To me, he is a very good writer, particularly of short stories. A couple of them have been translated into English, but he remains largely unknown here in the US.

Alison Lewis: I think there are a lot of overlooked authors out there who are worthy of greater attention from English-language audiences. Frayed Edge Press recently published two early works by the Norwegian author Jens Bjørneboe. He was a mid-twentieth century writer, and if he had not been writing in a “minority language,” I believe his work would be held in the same regard as Thomas Pynchon and Günter Grass. We are open to publishing translations and welcome suggestions for authors who, like Seligson, maybe a bit “on the fringe.”

Nidhi Ajay: Would you consider more of Esther Seligson's translations in the future?

Selma Marks: I am presently translating Seligson's La morada en el tiempo.

Alison Lewis: From the press’ perspective, the answer would be an enthusiastic “Yes!”

Please support the phenomenal work Frayed Edge Press is doing, you can find all of their work here. Please let us know what you thought of this piece, if you are new here - consider subscribing - it doesn’t cost a penny and it helps me amplify voices of women who are fucking phenomenal. Roar - like - a - LADY